Understanding Employer Equity

Equity compensation is a powerful tool for motivating and rewarding your team, but it's essential that you get the details right. Let's dive into everything you need to know about employer equity.

Published 5.12.2023

/

Updated 1.10.2024

Besides the free backpack, soundbar, and t-shirt, how is a company to incentivize its employees? Isn’t a paycheck enough!? Not anymore! To retain high-performing employees, equity has become an important component for many companies, especially start-ups. We’ll unpack the most common forms of equity for you, and our recommendations for each.

Basics of Employer Equity and Stock Options (ISOs and NSOs)

The most common form of employer options is formally known as “Incentive Stock Options,” or ISOs (different from NSOs). ISOs are given to you as a benefit by your employer to participate in the future growth of the company.

NSO’s, or non-qualified stock options are stock options that do not qualify for favorable tax treatment for the employee. ISO are only awarded to employees, whereas NSOs can be awarded to whomever. The main difference between ISOs and NSOs, however, is tax treatment. We’ll address tax implications for employer equity later, but unlike with ISOs, where you don't pay taxes upon exercise, with NSOs you pay taxes both when you exercise the option (purchase shares) and sell those shares.

There is usually a vesting schedule associated with options. “Vesting” with regards to equity means you earn your shares over a period of time. Options typically vest over a number of years. Once vested, you have the option to buy the shares at a discounted rate (the strike price). When you sell the equity (after an IPO, in a private equity market like EquityZen or SharePost, or back to your company) your profit will receive tax-beneficial treatment (if you meet a few requirements).

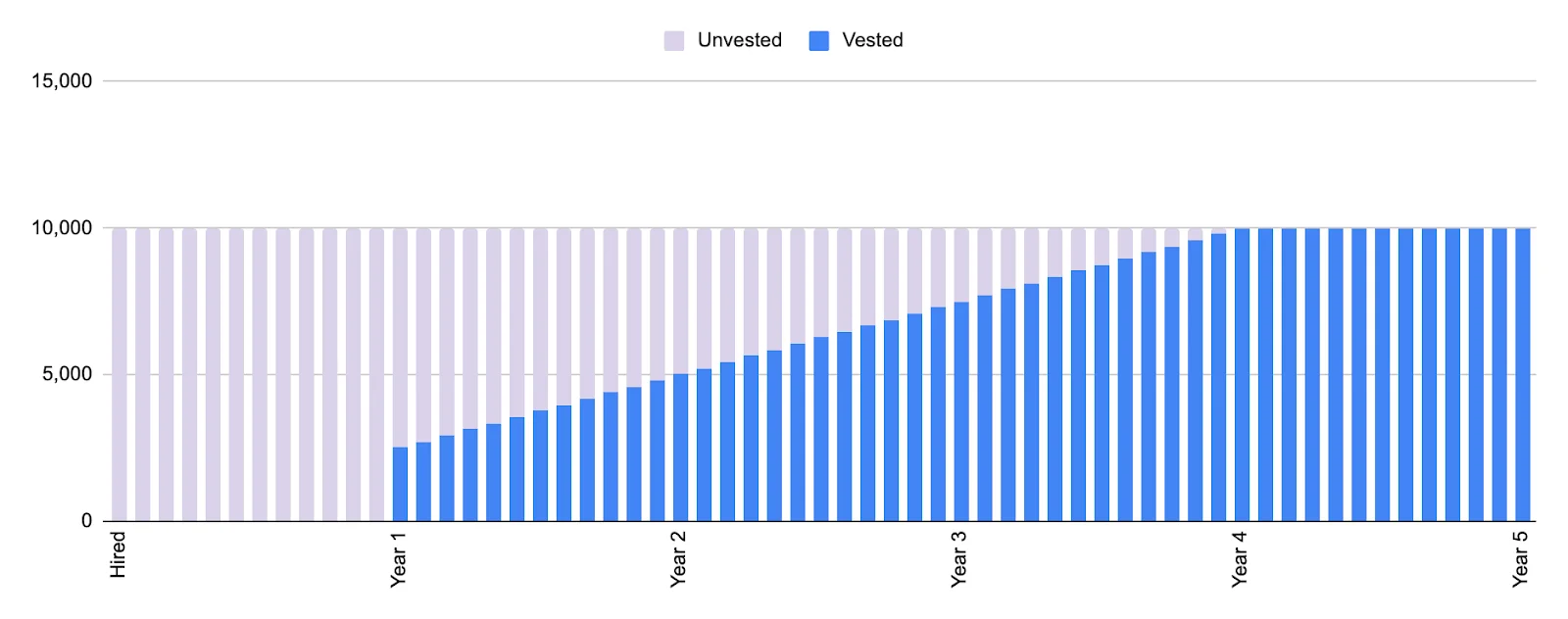

A standard 4 year vesting schedule with 1-year cliff for 10,000 shares would look like this:

For the first year of service, you own zero options. On your first anniversary, you will receive 25% of the shares you were granted and then incrementally more over the coming months until you reach 4 years. If you leave your company at any point before the 4 years, you lose any unvested shares.

How much are my options worth?

When we talk about the “current value” of the stock it may make sense where to get that value when the company is already publicly traded. But what about pre-IPO companies? If it has not gone public, the price is likely based on the latest 409A valuation. You will see a new valuation with each round of fundraising and it’s important to pay attention to the new value. The 409A valuation, like a stock value on the public exchange, will tell you the current value of your equity per share. 409A appraisals are done by an independent party and are presumed to be a ‘reasonable’ valuation of the equity by the IRS. If your company gets acquired, however, the price per share will be negotiated into the deal and you likely won’t have any advance warning about what that price might be.

When should I exercise?

When to exercise is based on a number of factors, part of which are out of your control. Before we go through a few scenarios it’s important to note that employee shares are usually restricted from being sold in the first 6 months after an IPO. Typically when this lockup ends, there are more sellers than buyers (employees offloading their shares) which may drive the price down. It’s usually about 3 months from the time a company files with the SEC to go public and when the shares trade publicly.

In almost ALL scenarios it’s important to work with a tax professional in the year you exercise because if there are additional taxes at exercise you may not account for this and then have a large tax bill you can’t afford.

If your company is public and you still have unexercised options, we would recommend exercising immediately if you can cover any potential AMT the following tax season (April) and selling the equity a year later. If you cannot come up with the AMT next April, wait til the next January to exercise, sell the following January, and you will have proceeds to cover your tax bill.

If your company is about to go public we would probably recommend exercising around the date your company files with the SEC (if you can cover the AMT payment next April with your current assets), or waiting until the following January (to be able to use future proceeds to cover your AMT).

If your company is not about to go public, but there is a private equity market for the shares (EquityZen or SharePost), you have the choice of starting to offload some shares (exercise next January), or just waiting for an IPO.

If your company is not about to go public and there isn’t a private equity market for the shares, you might as well wait, and preserve the optionality of your option. Sometimes people will like to slowly exercise (staying below the AMT threshold) to start the 1 year clock on some of the equity.

If your company is brand new and you’re an initial employee, it might only cost a few thousand dollars to early exercise using an 83(b) election, that could be worth it.

How do RSAs work?

With a restricted stock award (RSA), the employee has the right (if they want) to purchase equity in the company for fair-market-value, a discount, or nothing, depending on the documented terms. The employee owns the stock immediately, but it is held in escrow until it fully vests (and if you leave the company early they will buy the unvested equity back from you).

I actually have RSUs, how do they work?

RSUs, or restricted stock units, are promises made by your company, to give you shares in the future, typically on a vesting schedule (there can sometimes be other conditions, like performance). You do not own the shares immediately at the grant, you must wait for vesting. If you leave the company before the RSUs vest, they are forfeit.

Employee Stock Purchase Plans

Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs) involve purchasing equity from your employer at a discount (in larger publicly traded companies). You’ll typically contribute to an ESPP from payroll deductions (after-tax money) at a predetermined interval (like 6 months). Those deductions are used to buy your company’s stock at a discount (up to 15% off). As with RSUs, your diversification can suffer with regular contributions to an ESPP so consider selling the shares as soon as you purchase them. If you hold the stock longer, when you sell you will still pay ordinary income tax on the discount and capital gains on any increase in share price above that.

Isn’t there another one?

Finally, we have ESOPs (Employee Stock Ownership Plans), which are pretty interesting. They try to do multiple things simultaneously:

Provide a way for owners to sell their equity/create an internal market for the equity of closely held companies,

Give employees equity ownership while they work for the company,

Increase retirement savings of employees.

From the employee’s perspective, your employer contributes company stock to a pre-tax retirement account (similar to a pre-tax 401k) for you (subject to a vesting schedule). When you leave the company, your employer buys the equity back from you, leaving cash in this pre-tax retirement account, which you can then roll to a pre-tax IRA. Though you don’t keep the equity after you leave, it is a nice bonus in your retirement account that you don’t have to pay for.

Phew! That was a lot, I know. Congratulations on getting to the end! If this hasn’t quenched your thirst for employer equity information, we also walk you through taxation to help you understand the tax treatment of each type of employer equity, including the implications of different exercise scenarios.